In the twilight of life, a black ribbon emerges from a frame and coils itself inside the mind of one of the great French chroniclers of the internal. Across the world, a young girl stares at an image in a book: a woman, naked but for slippers, jewels, and the same ribbon which so captivates the writer. At opposite poles of experience, one follows the ribbon as it winds its way round longings, regrets, and contemplations; the other, at the beginning of development and yet to discover the world, traces the ribbon with a finger, not realising how it will imprint itself upon her.

Years later, the girl—now woman—encounters the ribbon face to face and on the page. Manet’s Olympia and the words of Michel Leiris come together, and an imaginary conversation ensues. It will be a collision and collaboration of sensorial memories and observations on everything from desire and illness to writing and grief. These frames are used to examine both interlocutors; simultaneously, a frame of another sort is removed from Olympia and her artistic kin. Everything from her flowers, Louise Bourgeois’s Sainte Sébastienne, and Francis Bacon’s Henrietta Moraes are reimagined and given new regard.

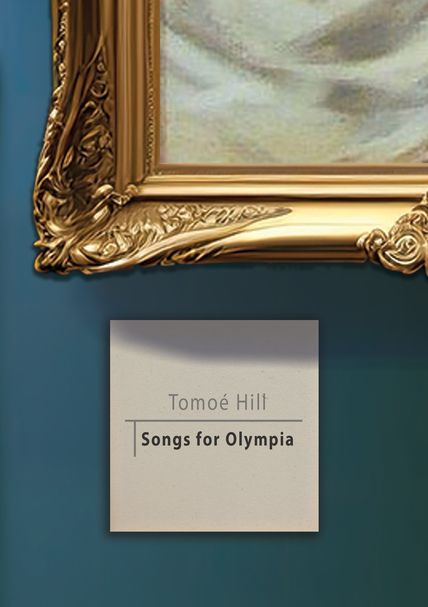

Songs for Olympia, written in the form of a response to Michel Leiris’s The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat, itself a highly personal response to Manet’s painting, is an ode to the both the ribbon and the memory: what leads us to constantly rediscover ourselves and a world so easily assumed as viewed through a single frame.

Notices

“Tomoé Hill brilliantly weaves heightened sensual-critical responses to painting and writing, fabric and memory, reading and desire, nudity, scent, jewellery, family, the giving of gifts, the finding of photographs, the making of meaning and all those fine dark forgotten ribbons that bind them loosely together. Songs for Olympia is pungent, shimmering, lush and intimate, at once resistant to anything as prosaic as interpretation and dizzyingly revelatory.”

—Tom Jeffreys, author of The White Birch and Signal Failure

“An intimate compendium of being in the world, Songs for Olympia unravels before the reader, in a language akin to the rhythms of the heart, the many ways of the body, the many lives of the mind, the many echoes of the voice. In one frame after another, following the circular black ribbon as if it were a thread through the labyrinth of memory, the book becomes what the author herself sees in Manet’s painting: something that holds a mirror before its audience. What begins as a conversation with Leiris ripens into a conversation and collaboration with the self and with the Other; a confluence of reflection and the reflected, where one no longer knows what is written—read—and what is remembered. This likeness, this manifold examination, grows and grows with each page, like a canvas that breathes and expands itself while it is being painted on. Tomoé Hill’s observations rush through the mind and stitch themselves to its walls, offering something for the psyche to feed on, something for the self to recognize itself in, something for the senses—something of everything, whether philosophical, corporeal, or glimpses of everydayness. Songs for Olympia is raw, and real, and necessary. ‘We explain the world by what we observe,’ writes the author, and in giving the reader this thought, imbued with instances of life, of seeing and being seen, of light and darkness, of being and becoming, the book takes on the shape of a world in itself—a world personal not only to the author, to Manet, or to Leiris, but to anyone reading its pages.”

—Christina Tudor-Sideri, author of Disembodied and Under the Sign of the Labyrinth

“Songs for Olympia is an extraordinary conversation between Michel Leiris’s ekphrasis in The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat and Tomoe Hill’s own. Swiveling between literary criticism, art history, memoir, and speculative nonfiction in this ‘response to a response,’ the speaker observes the subject in the refractions of Manet’s Olympia in the intertextual action instantiated by multiple addresses. ‘Like all women thus framed,’ she encounters herself in the mirror of others’ judgments, that ‘mark of Olympia’ wound round her throat. There is the image, the self, the self-as-subject, the memory, and the author. And there is the fetish symbolized by the little black ribbon.

“Against the value of Olympia’s ‘emptiness’ as envisioned by men, Hill seeks proper nouns and particulars, a subjectification rather than an erasure. Call it a portrait with a pulse, a lexicon of close attention rooted in reciprocity, or a book that embodies the tenderness of acknowledgement in counterpoint to the ossified re-creation. She wonders, for example, if Victorine (Manet’s model) recognized herself as the subject in the painting; she analyzes the particular hue of Olympia’s lips and tries to match it to lipstick. ‘We explain the world by what we observe,’ the speaker says, carving each observation in its relation to Olympia before returning to Leiris with his own words. Tomoé’s sensibility involves looking closely—and then closer. She wonders why Leiris refers to the doll in Hoffman’s Sandman without mentioning that the doll’s name is also Olympia. What does it mean to leave the doll who can only say ‘ah ah’ unnamed? In formalizing desire, fetish complicates identification. Theorizing at a slant, the speaker longs for an ‘aesthetic precision’ in self-identification. As a child, the speaker lacked a context in which to read her mother’s kimono outside the Japanese house. Tomoé Hill’s response to Leiris’s gaze gives us an Olympia as a mirror in which the writer (a savior of courtesans and sex workers ‘who cannot admit he owes his own transformation to women’) viewed himself. Maybe Michel Leiris built himself a labyrinth so that he could be the Minotaur at its center. Certainly, I could sit in a room and watch myself watching Tomoé disarm his ghost’s gaze forever.”

—Alina Stefanescu, author of Dor

“Tomoé Hill’s Songs for Olympia is utterly brilliant, intimately confessional yet fiercely intellectual, insistently feminine, and outrageously playful (who knew what poetry lurked in the marketing names for lip gloss and perfume?). Her focus is Manet’s scandalous nude Olympia (nude but for a black ribbon at her throat). Her foil is the late great Michel Leiris who reflected on Manet’s painting in his 1981 book The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat. Leiris also wrote a famous book about manhood, which makes him the ideal sparring partner for Hill’s verbal legerdemain. She gently chides him for fetishizing that ribbon, for a writing style that is more a peacock’s mating dance than inquiry. She quotes him, banters with him, and challenges him to word games, all the while positioning herself and Olympia as analogues in their defiant womanhood. ‘It is only that no one asked her or me about our dreams,’ she writes. For, inevitably, Hill herself is the subject of this exquisite book—her body, her childhood, her lovers, her hidden thoughts, her delicious ironies—and she is immaculately original.”

–Douglas Glover, author of The Erotics of Restraint: Essays on Literary Form