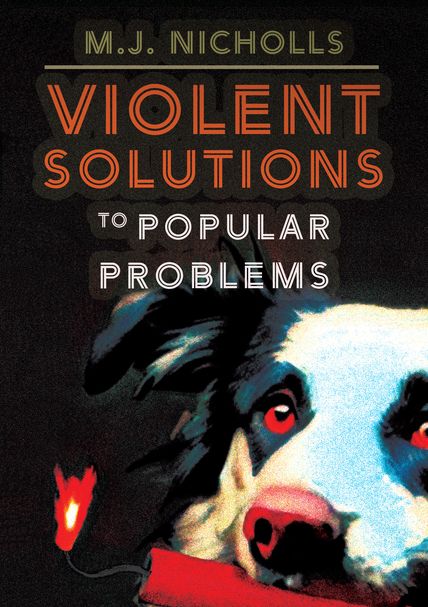

Extracted from the maw of a resting shrew, these ten cankers reek of huff and qualm. A librarian teams up with a weeping bus-dweller to suppress a talentless writer. A man attempts a perfect equilibrium of pain and pleasure to forge a life of matchless keel. A triumvirate of Dans spiral into oblivion with operatic panache. Two sub-people struggle for ascension to the normal realm in a heckish caste system. Various narked sods explain the violent solutions to their popular problems in a tale that Butch Vig might call “titular”. Someone explains the complex sociological web of mayhem that is the modern coffeehouse. Postmodernism makes a shocking return in a classic postmodern tale about postmodernism shaking its postmodern bahookie. In future Texas, women attempting abortions are held captive and forced to whelp at gunpoint. And in a finale one Dutch arborist has called “a botched stew”, the world’s unwritten characters mingle in a bardo where their untold stories flex and throb in painful collocation. For the first time in his life, the unacclaimed novelist M.J. Nicholls has written a collection of prose fit for hexagonal man.

Notices

“Through absurdist world-building (and then toppling), urbane cringe-humor told with the dead-eyed stare of a master provocateur, and the kind of metafictional flourish that’ll have you seeing stars as though a Chuck Jones anvil fell on your head, Violent Solutions to Popular Problems pulls the wings off literary convention with anarchic glee. M.J. Nicholls is contemporary literature’s greatest prankster, and we’re all the better for living in a world where he’s laughing at us, rather than with us.”

–Jeff Chon, author of Hashtag Good Guy With a Gun and This Is the Afterlife

“Nicholls’ recklessly inventive books … have earned him critical plaudits as a writer who is playful but political: an absurdist with one foot planted firmly in the real world. He’s a comic novelist at heart, so his fascination with postmodernism is impish, provocative, irreverent. If there’s one thing Nicholls doesn’t seem to have time for, it’s realism. Why make do with dreary naturalistic dialogue when a character grandly declaring her home to be ‘the topological crumbs of Orkney’ is so much fun? … [T]his fertile, febrile imagination is constantly in motion, and there are no signs of it slowing down.”

—Alastair Mabbott, in The Herald Scotland